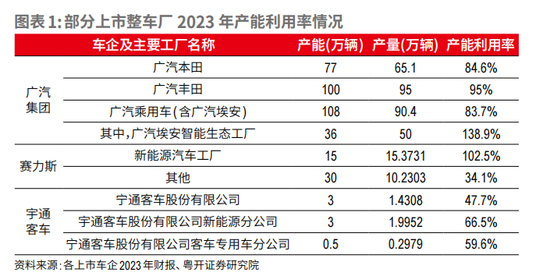

Our country’s new energy vehicle production capacity utilization rate is generally around 80%, which is at a normal level. There is no overcapacity in lithium batteries and photovoltaics. Although the utilization rate has declined significantly and some companies are facing operational difficulties, it is mostly due to temporary and structural supply-demand imbalances. Measures such as expanding domestic demand and going global may help address the situation. The “new three items” represented by new energy vehicles, lithium batteries, and photovoltaic products have become important symbols of China’s manufacturing moving towards high-end, intelligent, and green development. However, the rapid development has also led to discussions about overcapacity in these areas. Let’s first review historical overcapacity and make comparisons. In the past two severe cases of overcapacity, China experienced serious overcapacity in 1995-2001 and 2011-2016. With the joint efforts of various regions and sectors, the elimination of overcapacity and risk mitigation have been largely completed, and supply-side structural reforms have achieved significant results. After the reform and opening up, China’s first severe overcapacity occurred from 1995 to 2001. At that time, as industrialization accelerated, the country shifted from a “shortage economy” to a “buyer’s market” where supply exceeded demand. Due to inertia in thinking and existing systems, overcapacity was not promptly reversed, leading to the situation. The causes of this round of overcapacity are threefold: first, since the reform and opening up, there has been inertia in investment growth and supply expansion, coupled with a rapid decline in demand due to the Asian financial crisis, leading to a mismatch; second, the investment and financing mechanism is not sound, resulting in a high concentration of investment due to the phenomenon of an “enterprise surge”; third, the marketization level of enterprise operations is insufficient, and the exit channel for state-owned enterprises’ production capacity is blocked. The second round of severe overcapacity occurred from 2011 to 2016, with capacity utilization, market prices, and business profits all significantly declining, similar to the first round of severe overcapacity. The causes of this round of overcapacity are complex: first, after the 2008 international financial crisis, the “four trillion” investment plan and real estate stimulus policies led to rapid expansion of infrastructure and manufacturing investment, driving rapid expansion of capacity in steel, cement, glass, and other industries; second, local governments actively promoted and blindly stimulated redundant investment; third, changes in population, environment, and other resource endowments, as well as the transition of domestic economic development stages and the slowdown in demand growth; fourth, distorted allocation of financial and other resources towards overcapacity areas, with zombie companies lacking exit channels, leading to a vicious cycle of “more subsidies, more losses, more losses, more subsidies”; fifth, the characteristics of small, scattered, and weak industries make it difficult to cope with macroeconomic shocks. In comparison, there are significant differences in the industries affected by the first two rounds of overcapacity. The first round of overcapacity mainly occurred in consumer goods industries such as textiles, household appliances, film, and telephones, mainly in the midstream and light industries, with incremental demand saturating, consumer groups shifting towards updated products, and a significant decrease in capacity utilization. The second round of overcapacity mainly occurred in raw material industries such as steel, cement, flat glass, electrolytic aluminum, polysilicon, and some equipment manufacturing industries, mainly in the upstream and heavy industries. The completion of the steel capacity reduction work in 2021 marks the confirmation of the results of resolving excess steel capacity. In recent years, the “new three items” represented by new energy vehicles, lithium batteries, and photovoltaic products have become important symbols of China’s manufacturing industry moving towards high-end, intelligent, and green development. In 2023, the export of the “new three items” broke through the trillion yuan mark, growing by 29.9%, significantly higher than the overall export growth rate of 0.6%. But the rapid development and competitive advantage of China’s new energy industry have raised concerns and suppression from Western countries such as Europe and America, triggering a new round of discussions on “overcapacity.” Since April, Europe and America have baselessly accused China’s new energy industry of overcapacity due to government subsidies. On May 14, the United States announced tariffs on $18 billion worth of products imported from China, including electric cars, power batteries, and solar panels, with electric cars facing a total tariff rate of 102.5% starting from August 1. On June 12, the European Union announced tariffs on electric cars imported from China starting in early July. The stigmatization of China’s “overcapacity” by Europe and America fundamentally stems from their own trade protection and industrial protection, violating the basic principles of free trade and market competition. Our research shows that there is no overcapacity in China’s “new three” areas. In the field of new energy vehicles, there is no overcapacity in China, but there is fierce competition. Recent years have seen China’s new energy vehicles maintain a strong momentum in production and sales, creating favorable conditions for the industry to achieve a “leapfrog” development. According to data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, in 2023, China’s production and sales of new energy vehicles reached 9.587 million and 9.495 million respectively, ranking first in the world for nine consecutive years. The production and sales increased by 35.8% and 37.9% respectively compared to the previous year, accounting for 31.6% of all car sales, an increase of 5.9 percentage points from 2022. China’s new energy vehicles do not have the overcapacity as claimed by Western countries, reflected in four aspects. First, according to the Shenwan industry classification, there are 22 listed companies involved in car manufacturing, with 12 disclosing the utilization rate of new energy production lines, averaging 81.5%, which is at a normal level. Some car companies’ new energy production lines are even operating at overload. 1. GAC Group’s GAC Aian Smart Eco Factory has a capacity utilization rate of 138.9%, while GAC Honda Factory is only at 84.6%, and new energy vehicle company BYD’s capacity utilization rate is even higher at 160%. 2. GAC Group’s GAC Aian Smart Eco Factory achieves a capacity utilization rate of 138.9%, while GAC Honda Factory is only at 84.6%, and new energy vehicle company BYD’s capacity utilization rate is even higher at 160%. 3. GAC Group’s GAC Aian Smart Eco Factory uses 138.9% of its capacity, GAC Honda Factory uses only 84.6%, and BYD’s capacity utilization rate is 160%. 4. GAC Group’s GAC Aian Smart Eco Factory reaches a capacity utilization rate of 138.9%, while GAC Honda Factory is at 84.6%, and new energy vehicle company BYD’s rate is even higher at 160%.

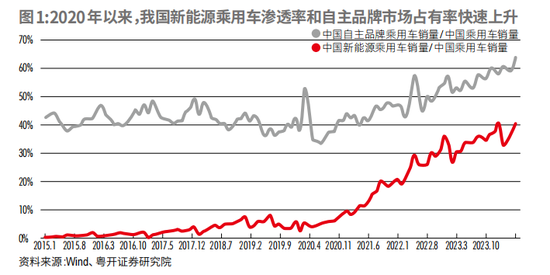

Second, China’s new energy vehicles are mainly for domestic sales, with exports accounting for a small percentage. In 2023, China exported 1.203 million new energy vehicles, only 12.5% of total production, mainly to meet domestic demand. In contrast, Japan’s car exports in 2023 were about 4.42 million units, accounting for 49.1% of domestic car production, with nearly half for export. Third, the overseas selling price of China’s new energy vehicles is higher than the domestic price, unrelated to dumping. According to Jiemian News, the mainstream pure electric vehicle models exported from China have higher prices in the European market than domestically. For example, the first global model released by BYD in 2022, the BYD Atto 3, has a domestic price of about 139,800-167,800 yuan (23090$), while the European price is 377,000-970,000 euros, nearly doubling overseas. Fourth, China’s competitive advantage in new energy vehicles comes from continuous innovation and strong product capabilities. With the penetration rate of new energy passenger vehicles in China increasing from 6% in 2020 to 34.6% in 2023, the market share of domestic brands in passenger vehicles increased from 38.4% in 2020 to 55.8% in 2023, further rising to 60.7% in January-April 2024. The market share of traditional fuel vehicles, foreign-funded, and joint venture car companies has significantly declined.

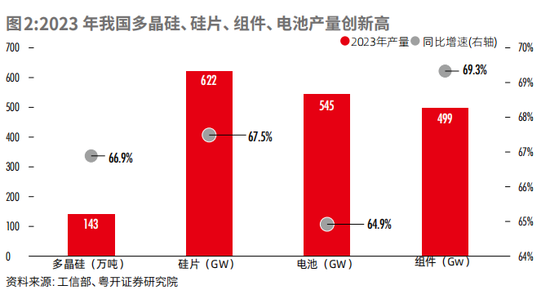

Currently, the domestic new energy vehicle market faces fierce competition with over 150 active brands. Data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers shows that the market share of the top ten enterprise groups in car sales in 2023 decreased by 1.7 percentage points compared to 2022. According to the China Passenger Car Association, in the first quarter of 2024, 67 models saw price reductions, with 55 of them being new energy models. The price reductions are driven by cost reductions resulting from technological advancements and economies of scale. In the lithium battery industry, China’s global market share for power batteries exceeds 70% and for energy storage batteries exceeds 90%. The country’s international competitiveness is continuously increasing, with Chinese companies occupying 6 seats among the top 10 battery manufacturers by installed capacity. In terms of exports, in 2023, China’s cumulative exports of power and other batteries reached 152.6 gigawatt-hours, accounting for about 20% of total production. Of this, power batteries accounted for 83.5%, with cumulative exports of 127.4 gigawatt-hours, a year-on-year increase of 87.1%. In terms of value, the cumulative export value of lithium batteries reached $65.01 billion, a year-on-year increase of 27.8%. The United States remains the largest export market, with exports totaling $13.55 billion, a year-on-year increase of 33.9%, accounting for 20.8% of China’s lithium-ion battery exports; followed by Germany and South Korea, accounting for 14.4% and 12.1% of China’s lithium battery exports, respectively. Globally, with the continuous promotion of green and low-carbon development, the demand for new energy vehicles continues to grow, coupled with policy guidance and technological innovation by enterprises, China’s lithium battery industry has established a strong international competitive advantage. By 2023, China’s lithium-ion power battery shipments will account for over 70% of the global market share, with the energy storage battery sector exceeding 90%. Major battery manufacturers’ market shares are still rising globally. According to South Korean research firm SNE Research data, in the first quarter of 2024, the global installed capacity of power batteries reached 158.8 gigawatt-hours, with 6 Chinese companies among the top 10 manufacturers in terms of installed capacity, with CATL and BYD occupying the top two positions. The previous pattern of the lithium battery industry being dominated by China, Japan, and South Korea has basically become a situation where Chinese companies are dominant. However, since 2023, the capacity utilization rate of companies in the lithium battery industry chain has significantly declined, with prices of battery cells and lithium salts dropping by over 50%. Some companies are beginning to face operational difficulties. According to Gao Gong Lithium Battery statistics, in 2022, the overall capacity utilization rate of China’s lithium battery industry was about 76%, dropping to around 50% in 2023, and in February 2024, the capacity utilization rate was between 35% and 45%. The temporary supply-demand imbalance in the battery industry also directly affects upstream battery material companies, with the cathode material capacity utilization rate remaining at around 40% in 2023. In terms of prices, data from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology show that in 2023, there was a significant decrease in lithium battery industry product prices, with battery cell and battery-grade lithium salt prices dropping by over 50% and 70%, respectively. In recent years, the revenue and net profit growth rates of listed lithium battery companies have declined. Among the 32 lithium battery listed companies in the Shenwan industry classification, the year-on-year growth rates of operating income and net profit in 2023 were 15.6% and 18.2%, respectively, a decrease of 80.5 and 40.7 percentage points compared to 2022. Additionally, the number of loss-making companies has increased, and industry differentiation is evident. Compared to 2022, 4 companies went from profit to loss, and 27 companies saw a decrease in net sales margin, with over 80% of the lithium battery industry concentrated. According to data from the China Automotive Power Battery Industry Innovation Alliance, the market share of the top 5 companies in terms of installed capacity is 86%. Second and third-tier manufacturers are facing operational difficulties due to overcapacity, lack of customers, and cost disadvantages, with their survival space worrying. Currently, the lithium battery industry is facing a phase of structural supply-demand imbalance, mainly due to the need to update and renovate some old production capacity that cannot be effectively utilized, while high-quality new production capacity is insufficient to fully meet market demand. For example, in terms of application scenarios, 4C fast charging batteries continue to increase in volume; in terms of form, large cylindrical batteries are ready to be launched, with planned production capacity exceeding 300 gigawatt-hours; in terms of materials, there is still a gap in high-nickel ternary and lithium iron phosphate batteries. However, there is a certain degree of oversupply in low-nickel ternary and ordinary lithium iron phosphate batteries. As the industry enters a mature stage, the industry landscape will be reshuffled, with advanced capacity replacing backward capacity, and the supply-demand imbalance will gradually improve. In the solar photovoltaic sector, China has become the country with the largest market size, the most complete industrial chain, and the strongest competitiveness. The scale of applications and manufacturing continues to grow. In terms of applications, according to data from the National Energy Administration, China’s new solar photovoltaic installed capacity reached 216.9 gigawatts in 2023, ranking first globally for 11 consecutive years, with a year-on-year growth of 148.1%. The cumulative installed capacity reached 609.5 gigawatts, ranking first globally for 9 consecutive years. In terms of manufacturing, according to the International Energy Agency’s report “Advancing Clean Technology Manufacturing,” around 80% of global solar photovoltaic manufacturing is concentrated in China, with India and the United States each accounting for 5%, and Europe only 1%. Among them, China’s silicon wafer production capacity accounts for about 95% of global capacity, multicrystalline silicon production capacity accounts for 96%, and component production capacity accounts for 83%. In 2023, China’s production of multicrystalline silicon, silicon wafers, cells, and modules reached new highs, with annual growth rates exceeding 60%, and the industry’s total output value exceeding 1.7 trillion yuan. Half of China’s solar photovoltaic products are exported, with the main export markets being Thailand and Vietnam in Southeast Asia, as well as the Netherlands in Europe. The reason for focusing on these countries is their strong re-export trade capabilities, with the four Southeast Asian countries targeting the US market and the Netherlands targeting the European market. Most top solar companies in China have overseas warehouses or forward warehouses in the Netherlands to facilitate shipments for European distributors.

In recent years, the strong expectation of global carbon neutrality targets has led to a large influx of social capital into the photovoltaic industry. Photovoltaic companies pursuing vertical integration have replicated the missing production capacity in the sub-segment chain, resulting in a rapid accumulation of production capacity. The IEA points out that currently the global utilization rate of solar cell and module manufacturing capacity is about 50%, with China’s utilization rate around 50-60%. The continuous oversupply has led to a decrease in prices of photovoltaic products, with prices of domestic polysilicon and module products dropping by more than 50% in 2023. The export of photovoltaic products has also shown a trend of “increased quantity and decreased price.” According to data from the General Administration of Customs, in 2023, China’s export value of photovoltaic main materials was $49.07 billion, a decrease of 5.5% from $51.91 billion in 2022. Since June, the year-on-year growth rate has remained negative. In terms of quantity, silicon wafer exports reached 7.91 billion pieces, an increase of 41.1% year-on-year; cell exports reached 5.21 billion pieces, an increase of 43.5% year-on-year; module exports reached 430 million pieces, with a slight decrease year-on-year and a growth rate of -2.5%. The photovoltaic industry is currently facing both temporary and structural issues, and this is not the first time that supply and demand imbalances have occurred. The current industry trend is the rise of N-type cells and the gradual phasing out of P-type cells. The transition in technology routes will inevitably involve the clearance of outdated production capacity and the upgrading of high-quality capacity. The key is that in the past, when China faced supply and demand imbalances in emerging industries like photovoltaics, it accumulated certain policy experience. The last round of supply and demand imbalances in the photovoltaic industry occurred around 2013, mainly due to the European debt crisis leading to subsidy cuts and a decline in overseas demand, compounded by the “double reverse investigation” in Europe. At that time, industry utilization rates dropped to below 30%, and even leading companies like Suntech in Wuxi went bankrupt and restructured. In July 2013, the State Council issued the “Opinions on Promoting the Development of the Photovoltaic Industry,” followed by various ministries formulating implementation plans. With the gradual effectiveness of various policies, the prosperity of the photovoltaic industry is gradually stabilizing, and China’s photovoltaics are gradually transitioning from an extensive growth stage to an intensive development stage. Five main reasons for the imbalance of supply and demand in the new energy industry: First, emerging industries have broad prospects and are prone to “rush in.” New energy is a typical emerging industry with a large market potential and broad growth space, attracting not only continuous expansion and market share competition among industry enterprises, but also cross-industry investments from other companies trying to share industry dividends. Second, the rapid iteration of technology in emerging industries forces continuous capacity expansion. Current technologies such as lithium batteries and photovoltaic products are still in the exploratory and rapid development stage. Therefore, when new technologies emerge, existing production lines of enterprises may be outdated before they are put into operation or recoup their costs. These production lines cannot be transformed into advanced production lines, so companies can only build new production lines, leading to the difficulty of eliminating outdated capacity, continuous addition of advanced capacity, and constant expansion of total capacity. Third, the “bottom-up competition” for investment attraction by local governments has also promoted the disorderly expansion of industrial capital to a certain extent. Local governments compete to provide land, tax incentives, and other favorable policies to attract companies to invest and build factories locally in order to increase local GDP, employment, and fiscal revenue. New energy and other emerging industries conform to the direction encouraged by central policies and have become the focus of local government investment attraction. However, the homogenized industrial layout of local governments has led to a large amount of redundant construction. The preferential policies have reduced the cost of capacity expansion for companies, exacerbating the disorderly expansion of industrial capital that already has a tendency to “rush in.” In addition, it is easy to see phenomena such as local protectionism and corporate subsidy fraud. Fourth, although the future demand for emerging industries is broad, the current demand has not been fully released. Due to reasons such as unstable technology and inadequate supporting measures, a large number of consumers are still in a wait-and-see attitude. For example, there is range anxiety for new energy vehicles, the high volatility of photovoltaic power generation poses a risk to the stable supply of the power system, and lithium batteries still need to be improved in terms of safety, cycle life, and energy density. Demand is steadily increasing, but supply is rapidly released, resulting in an oversupply in the short term. In the context of economic globalization, the trade protectionism actions of Western countries have triggered or exacerbated global supply and demand imbalances. Exporting products with comparative advantages can enhance production efficiency and overall welfare. However, trade barriers set up by Europe and the United States have led to a contraction in foreign demand for other countries, a decline in exports, and oversupply in advantageous industries. This not only increases global supply and demand imbalances but also violates the principle of comparative advantage, reducing global production efficiency and harming domestic consumer welfare. If other countries follow the example of Europe and the United States in creating trade frictions, the United States’ commodities such as soybeans, shale oil and gas, and automobiles will also face overcapacity. The previous dilemma faced by China’s photovoltaic industry was partly due to European and American policy shocks. Six major policies can address the dilemma. The imbalance between supply and demand in the new energy industry may lead the entire industry into a dilemma of “profitless prosperity,” damaging the long-term international competitiveness of China’s industries, and must be promptly and properly addressed. First, in the face of unfair and unreasonable trade restrictions by Western countries, the government should fully utilize the WTO dispute settlement mechanism to weaken trade frictions, take targeted countermeasures within WTO rules in a timely manner, and enterprises should actively file complaints to safeguard their legitimate rights and interests. Second, enterprises should accelerate their “going global” layout. Previously, some of China’s new energy enterprises have transferred some production capacity to Southeast Asian countries, but still face trade protection restrictions from Europe and the United States. In order to smoothly enter the European and American markets, related enterprises can invest and build factories in their home countries, but they need to overcome difficulties in project approval, employee recruitment, supply chain management, and whether they can obtain local subsidies. The government should provide support in platform building, financing services, risk assessment, and safety guidance to help enterprises better internationalize their layout. Third, improve supporting measures and expand domestic demand. 1. Accelerate charging infrastructure construction, gradually lift restrictions on new energy vehicle purchases, unleash consumption potential; deepen power system reform, build new energy-based power system, boost demand for photovoltaic and energy storage. 2. Push forward charging infrastructure construction, lift restrictions on new energy vehicle purchases, unleash consumption potential; deepen power system reform, build new energy-based power system, boost demand for photovoltaic and energy storage. 3. Push charging infrastructure, lift vehicle purchase limits, boost consumption; deepen power reform, build new energy power system, boost demand for photovoltaic and energy storage. 4. Pushes infrastructure, lifts limits, boosts consumption; deepens reform, builds power system, boosts demand. 5. Push infrastructure, lift limits, boost consumption; deepen reform, build system, boost demand.

Fifth, focus on market orientation, government guidance, support leading companies in acquiring and restructuring troubled companies, increase industry concentration, facilitate market exit mechanisms, promote large-scale and intensive operations, improve supply and demand relationships, prevent excessive competition. Sixth, regulate local governments’ investment promotion policies, establish a unified national market. Optimize performance evaluations of local officials, transform the functions of local governments, prevent “race to the bottom” policies in investment promotion, avoid low-level redundant construction; break local protectionism and market segmentation, promote the smooth flow of commodity factors and resources on a larger scale, establish an efficient, standardized, fair competition domestic unified market. Any information mentioned in this article is solely the author’s personal opinion or statement on specific events, not a recommendation or investment advice, not representing the position of this publication. Investors should bear the risks and consequences of investing based on this information.